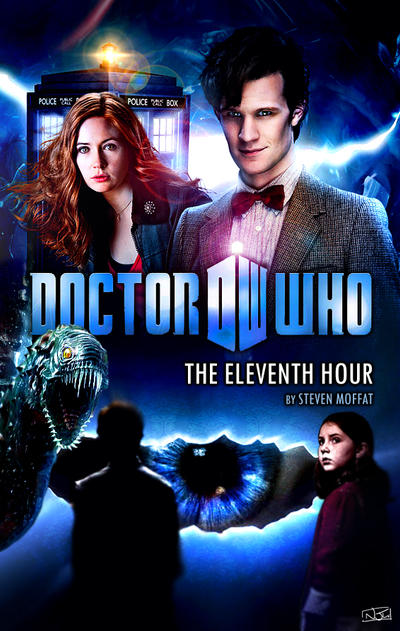

Following the whimsical fairy tale beginnings of “The Eleventh Hour” and the dystopian mysteries of “The Beast Below”, Doctor Who’s fifth season takes a sharp turn into familiar territory with “Victory of the Daleks.” Much like “Dalek” did for the Ninth Doctor’s era, this episode reintroduces the Doctor’s most iconic enemies – but with a twist that would prove controversial among fans.

The premise is deliciously simple: Winston Churchill has enlisted the help of mysterious “Ironsides” to fight the Nazi threat. These Ironsides are, of course, Daleks, painted in khaki green and serving tea while calling everyone “sir.” It’s an image as unsettling as the gas mask children asking “Are you my mummy?” – though for entirely different reasons. Where we expect hatred and extermination, we get subservience and helpfulness. The cognitive dissonance is perfect.

Matt Smith’s Doctor shines in this episode, his relatively new incarnation allowing for a fresh take on the Doctor’s deep-seated hatred of the Daleks. Unlike Eccleston’s traumatized survivor or Tennant’s vengeful warrior, Smith’s Doctor approaches the Daleks with an almost childlike rage – pure, uncontained, and dangerous. When he beats a Dalek with a comically large wrench while screaming “I am the Doctor, and you are the Daleks!” it’s both frightening and revealing. Like “Bad Wolf”, this episode shows us how the Doctor’s history with these enemies has shaped him.

The supporting cast is stellar, with Ian McNeice’s Churchill stealing every scene he’s in. His relationship with the Doctor feels lived-in, suggesting a long history we’ve never seen – much like the relationships hinted at in “Boom Town”. Karen Gillan’s Amy Pond continues to develop nicely, though her lack of recognition regarding the Daleks (given the events of “The Stolen Earth”) creates a mystery that would become significant later in the season.

But the real story here is the Daleks themselves. Their plan is typically convoluted yet brilliant: present themselves as humble servants to trick the Doctor into identifying them, thus activating the “Progenitor device” that wouldn’t recognize these time-war-surviving Daleks as pure enough to accept their commands. It’s a clever way to address both the in-universe need for more Daleks and the out-of-universe desire to redesign them.

The redesign itself proved controversial. The new “Paradigm” Daleks, with their Power Rangers-esque color coding and chunky design, represent a significant departure from the bronze warriors we’ve grown used to since “Dalek”. While the idea of a Dalek hierarchy based on function is interesting, the execution left many fans cold. It’s worth noting that this wouldn’t be the last time the show would attempt to reinvent its classic monsters – though perhaps with more success than here.

The episode’s World War II setting is used effectively, though perhaps not as immersively as “The Empty Child”. The threat of German bombers provides a constant background tension, while the moral question of whether Churchill should be allowed to use the Daleks as weapons adds philosophical weight to the proceedings. It’s reminiscent of the ethical dilemmas posed in “The Unquiet Dead”, where the question of whether to trust apparently helpful aliens drove the plot.

One of the episode’s strongest elements is its exploration of the nature of victory itself. The Daleks achieve their victory by essentially losing – allowing themselves to be abused and defeated by the Doctor to achieve their true aim. It’s a clever subversion of the usual “Doctor defeats Daleks” formula we’ve seen since “The Parting of the Ways”. Meanwhile, Britain’s eventual victory over Nazi Germany is presented as inevitable, yet the episode reminds us that in 1941, nothing felt certain.

The subplot involving Bracewell, the human scientist who turns out to be an android created by the Daleks, provides both emotional resonance and a clever resolution. Like “The Doctor Dances”, the power of human emotion and memory becomes key to averting disaster. The scene where Amy talks Bracewell through his “memories” to prevent his self-destruction is particularly touching, though it perhaps resolves too easily.

The episode’s climax, featuring a space battle between Spitfires and Daleks, is pure Doctor Who at its most gloriously ridiculous. Like the sword fight with Robin Hood in “The Robots of Sherwood”, it’s the kind of sequence that only this show could pull off with a straight face. The gravity bubble technology that allows World War II fighters to reach orbit is exactly the kind of pseudo-scientific nonsense that makes the show so much fun.

However, the episode’s ending is somewhat unsatisfying. The Daleks escape with their victory complete, leaving behind a rather hollow human triumph. While this sets up future appearances, it lacks the emotional punch of earlier Dalek stories like “Dalek” or the grand scale of “Bad Wolf”. The Doctor’s failure here feels less like a dramatic choice and more like a plot necessity.

Despite its flaws, “Victory of the Daleks” remains an important episode in the Smith era. It establishes this Doctor’s relationship with his oldest enemies, introduces design elements that would influence the show for years to come, and provides some genuinely entertaining moments. Like “The Beast Below”, it shows that the new production team isn’t afraid to take risks with established elements of the show.

The episode also continues the season’s underlying themes about memory and history. Amy’s inability to remember the Daleks, Bracewell’s artificial memories, and even Churchill’s selective view of how to achieve victory all play into the larger narrative about the nature of memory that would become crucial in episodes like “The Big Bang”.

While perhaps not reaching the heights of classic Dalek stories, “Victory of the Daleks” deserves credit for trying something new with Doctor Who’s most famous monsters. In a series that would increasingly focus on fairy tales and personal relationships, this episode reminds us that sometimes the old enemies are the best – even if they do get a controversial new paint job.